Another wonderful Christmas is in the books. I ate, drank

and made merry. Now it’s time to get back on track, and what better way to do

that than by reading a story?

|

| It's funny because it's true. |

I’ve been wondering about where the marathon originated for

a few weeks now, so here’s my take, based on minimal research and absolutely no

effort whatsoever:

The History of the Marathon:

Most of this story comes from Ancient Greece. Like many

tales that originate in those long-forgotten days, most of this tale is

probably romantic invention that was added, fabricated, and expanded upon by

later historians and chronicle writers. As such, this tale should be taken with

a shovel-full of salt because it’s closer to a Hollywood story than actual

history. The story of the modern marathon begins with a battle.

490 BC. Late summer. Greece. The desert-strewn plains of the

Marathon coast gleamed with swords and spears and shields. At one side of the

field stood the Greek army – hopelessly outnumbered, still awaiting the arrival

of their Spartan allies, who were at least ten days away. At the other end,

with the sea and a fleet of ships behind them, stood the Persian army – a mighty

force of conquerors and master tacticians who had never lost a battle. Things

looked grim for the Greeks. If they failed, all of Athens would soon fall to

Persia.

But luck was on the side of the Greeks that day. Many of

their warriors were hoplites – men armed with short swords and shields – and would

not have stood a chance against the much larger Persian army, especially not

with the cavalry lying in wait. No historian can agree on what triggered the

battle, but it seems that the Greeks lunged first. Perhaps the cavalry left the

field, or were moving into a more strategic position. Whatever the case, the horses

left the arena, prompting the Greeks to charge their enemy.

|

| A modern view of the battlefield. |

The Persians were not used to this sort of combat. They had

swordsmen and archers, yes, but most of their victories had come from keeping

the enemy at bay and crushing them with cavalry. Now that the battlefield was

even, the highly-trained Greeks were in control. They marched to the limits of

the Persian archer’s arrows and sprinted the remaining two hundred metres,

weighed down by metal helmets, leather armour, heavy short swords, and rounded

shields. This sudden lunge was either a surprise attack or a desperate gamble,

but it worked. The extreme edges of the Greek army made quick work of the

Persian flanks, then pressed in toward the centre, where the fighting was most fierce.

Nobody knows how long the battle truly lasted, nor how many

died (Herodotus says over six thousand Persians slain and only one hundred and

ninety-two Greeks, but history is written by the winners). In the end, the

Persians broke and fled back to their ships, awarding victory to the defenders.

This is a defining moment in western history – the first time the Persians had

ever been defeated, decades before 300 Spartans would achieve a similar goal.

The Persian global conquest was halted, possibly even foiled forever by this

one battle.

This is where romantic invention steps into the fray and

muddies the waters. A runner named Phillippides (who we shall call Phil to

spare my poor fingers) was tasked with hurrying back to Athens immediately

after the battle and informing the population of this stunning victory. Phil

dropped his helmet, sword, and shield and began running, clad only in his linen

undergarments and a pair of sandals. What’s the distance between Athens and Marathon,

you ask? Why, it’s twenty six point three miles exactly.

Phil raced across the dusty plains, feet thundering along

the ground, blood pumping hard in his ears. He ran and he ran and he ran, until

finally he reached Athens and burst into the council chambers. Then he either

shouted, ‘Joy to you, we’ve won!’ or ‘Joy, we win!’ to the stunned counsellors.

And you know what the world’s first marathon runner did next?

He-

fell-

down-

dead.

The story of Phil the marathon runner is likely a confusion

of two other similar events that took place around the same time as the Battle

of Marathon The first is a runner named Pheidippides, who was tasked with

asking the Spartans for assistance before the battle began. Pheidippides laced

up his sandals and raced to Sparta from Athens, a little over one hundred and

forty miles away. This is the same as running from London to Normandy, and he

managed it in less than thirty-six hours.

This event inspired the modern ‘Spartathon’ endurance challenge, a similar race

that takes place in Spain every year.

The second event is the massive return journey the Greeks had

to make immediately following the battle. Once victory was granted, the army

needed to get back to Athens right away – the Persians had sent ships around

Cape Sounion to attack the defenceless capital. That meant the army –

exhausted, bloodied, victorious – needed to march twenty six point three miles,

still clad in their armour, before the ships could dock and unload. They

reached Athens in the afternoon on that same day, just in time to watch their

enemies turn away from Athens and sail off into the sunset.

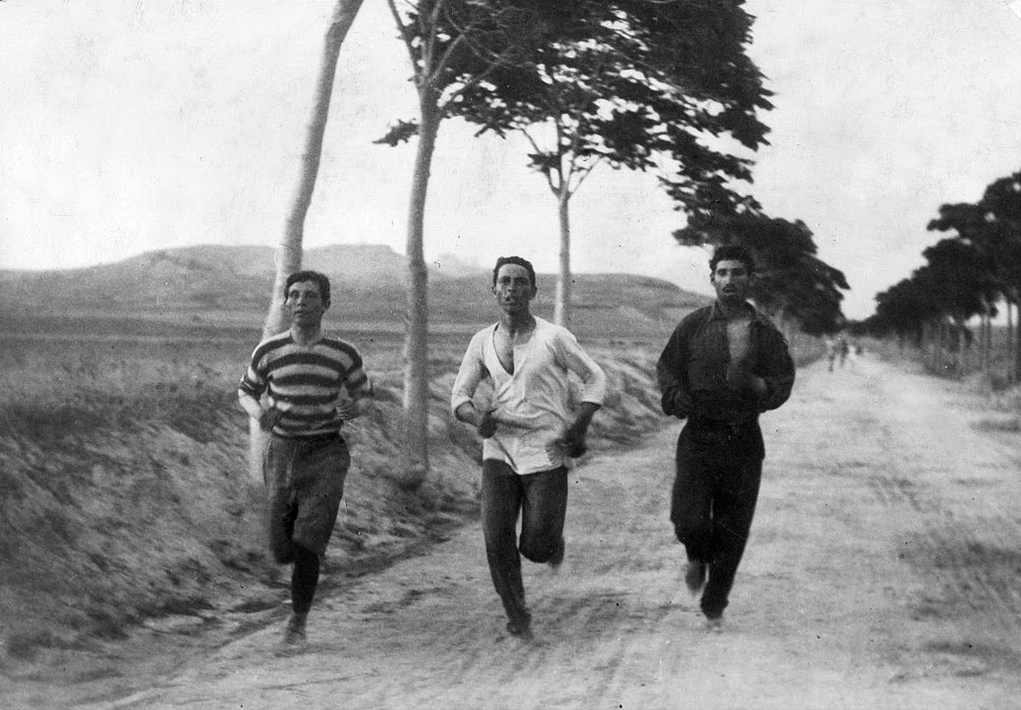

And that’s where the modern marathon comes from. This

legendary event was brought back into public consciousness in 1896, with the

very first modern Olympics, held in Greece. This event even traced the original

route, starting in Marathon and concluding in Athens. I have nothing but

respect for the runners who managed to complete that incredible course in those days. This

is what their training looked like:

|

| This was before anybody understood how to train or tone or condition the human body. This is all sheer willpower. |

Nowadays marathons are held almost every week across the

globe. Hundreds of thousands of people compete every year, running the same

distance as those legendary Greek warriors. I have to admit, the thought that I

could consider myself on par with the world’s greatest soldiers is an exciting

one. I might never have anything else physically in common with these people,

but I could compete in a similar endurance challenge. Maybe when I cross the

line, I’ll shout ‘Joy to you, we’ve won!’

Do I have any desire to take part in the Spartathon, you ask?

Um… no. Let’s try and do one ridiculous thing at a time, shall we?

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/165720348-56a12f6c3df78cf772683b39.jpg)